When I was first introduced to organized curriculum mapping our middle school team based our work on the model put forth by Dr. Heidi Hayes Jacobs’s Mapping the Big Picture (1997, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010).

There is a plethora of information in print and on the web outlining the concept behind mapping and detailing steps on how to implement a curriculum mapping initiative in your school. The following is a brief overview with resources to help you get started on your own curriculum mapping journey.

Curriculum Mapping is Not a Spectator Sport.

Curriculum Mapping tends to be a thorn in the side of many teachers who are asked to submit curriculum maps annually as part of their administrative ritual of accountability. These documents are usually recognized as good planning tools but then they are often deposited in binders where they are rarely used once the unit of study has begun.

A school’s curriculum mapping initiative must focus through a lens that looks at the balance between what was individually or collaboratively planned and the “on the ground” reality of what really took place in individual classrooms. This is “living” data and we measure it in real time: recorded by months or grading periods.

A good map is a window to let everyone know just what the heck is going on in the building.

The Journey is the Work: Teachers should never consider their maps as being “finished” nor is having maps the ultimate goal of mapping. Maps are the result of doing the hard, collaborate work of mapping. The term mapping itself is a verb – an action word that lets the school community know that the work is collaborative and ongoing. Mapping is a purposeful review process that will help teachers make instructional decisions based on what they have done before. That is why is it important that these be digital documents that can be easily shared (locally, nationally and internationally) and updated. These can be created in-house or using mapping software. Here are four links to examples of mapping software:

- MasteryConnect is a service that offers a good system for tracking your student mastery of Common Core standards. You can see the MasteryConnect curriculum mapping tool in the video found here.

- Atlas Curriculum Mapping– Rubicon International

- TODCM Web Based Curriculum MappingOpen Source Software …

- CURRICULUM MAPPER

School can create tailor-made, in-house formats as simple or as complex as deemed necessary:

***Click here for a simple mapping template that I made in Word. Whatever form a school uses it should be uniform and understood by all stakeholders.

Here is a GAHistory_Map_7th that is more complex and would ultimately need to be reviewed and edit with colleagues – especially with respect to paring down the essential questions. This map is actually two maps – one is an at-a-glance overview followed by more detailed maps outlining each unit.

Why Maps Must “Live”:

We are learning, and we are learning about learning. Schools will always have new students, new classes, and new school years and maps should be tailored, designed, revised, and replaced to reflect the evolution of learning.

This idea needs to be communicated and embraced by the whole staff. Curriculum maps are never to be used for teacher evaluation or punitive damage. Maps are designed to provide authentic evidence of what has happened or is being planned to happen in a school. This means school leaders must commit to the time it will take for teachers to engage and reflect upon the work. Leaders must walk the walk and invest the funds and the time necessary to execute a curriculum mapping initiative. This is no small task and should be built into a multi-year strategic plan BEFORE work begins. Otherwise, this can devolve into and exercise rather than a thoughtful pedagogical strategy.

THE 3 Cs (adapted from Mapping the Big Picture)

Communication

Curricular Dialogue

Coherency.

Communication — 21st Century curriculum maps are most often developed and maintained using an Internet-based commercial mapping system. This technological venue provides teachers and administrators with easy access to both the planned and actual horizontal (same grade level and/or same discipline) and vertical (different grade levels and/or different disciplines) curricula for present and past school years. The commercial systems’ search features allow teachers to gain instant information in regard to mapping data to aid in curricular dialogue. This means and level of communication is unprecedented. In the not-to-distant past data had to be printed out, copied, distributed, and an in-person meeting held to view and discuss the documents. Curriculum Mapping encourages innovation and thought about meeting differently and in new ways.

Curricular Dialogue — Teachers take part in collegial relationships wherein they make data-based decisions about grade-level, cross-grade level, disciplinary, and cross-disciplinary curricula and instructional practices. Teachers become Teacher Leaders. Curriculum Mapping has two guiding principles: Jacobs (2004) states that teachers and administrators must consider “…the empty chair…” which represents all students in a given school or district, and “…all work must focus on Johnny, and all comments and questions are welcomed as long as they are in his best interest” (p.2). Second, if it is in the students’ best interest to change, modify, stop, start, or maintain curriculum practices, programs, and/or other related issues, there must be data-based proof to do so (Jacobs, 2002). These two principles are logical, rational, and well-founded. One may consider them easy to implement, but oftentimes proves difficult in practice. Barth (2006) refers to the “…elephant in the classroom—the various forms of relationships among adults within the schoolhouse might be categorized in four ways: parallel play, adversarial relationships, congenial relationships, and collegial relationships” (p.10). Not surprising, the first three ways do not elicit vigorous curricular dialogue. Barth contends “…empowerment, recognition, satisfaction, and success in our work—all in scarce supply within our schools—will never stem from going it alone … success comes only from being an active participant within a masterful group—a group of colleagues” (p.13). Therefore, it is of utmost importance to provide teachers with ample professional development to hone their skills in all facets of curriculum mapping and collegial, curricular dialogue. Allowing teachers time to build personal ownership in the mapping process empowers them, and subsequently, improves student learning.

Coherency — A combination of 21st Century communication plus curricular dialogue eventually equals curricular coherency. Many teachers are currently engaged in what Dr. Jacobs (2001) refers to as “…treadmill teaching.” Running breathless on grade-level or content-area treadmills trying desperately to get everything they believe needs to be taught, taught. If teachers took the time to slow down their treadmills and personally document and evaluate both the planned, and most importantly, actual learning, they may well discover that they are perpetuating a potentially incoherent curriculum. Curriculum Mapping is designed to ask teachers to record, reflect on, study, and revise their individual and corporate work. This cyclic endeavor eventually leads a school or district to developing and maintaining an aligned curriculum that makes sense to all—and most importantly—to students!

From Mapping the Big Picture:

To make sense of our students’ experiences over time, we need two lenses: a zoom lens into this year’s curriculum for a particular grade and a wide-angle lens to see the K-12 perspective. The classroom (or micro) level is dependent on the site and district level (a macro view). Though the micro and macro levels are connected throughout a district, there is a conspicuous lack of macro-level data for decision-making. Yet we need that big picture for each student’s journey through his or her years of learning. With data from curriculum mapping, as the school and its feeding and receiving sites can review and revise the curriculum within a larger, much-needed contest. Data on the curriculum map can be examined both horizontally through the course of any one academic year and vertically over the student’s K-12 experience (pp. 3 – 4).

MAPPING THE ESSENTIAL QUESTION: Hard to write but essential with respect to framing a unit of study or course or both.

Dr. Joe Krajcik, a professor of science education at the University of Michigan’s School of Education, recommends the following list of characteristics as a guide to use when developing essential questions (Krajcik, Joe. “Characteristics of Driving Questions.” [Online]

Essential questions should:

- frame the organizing center

- promote higher order thinking

- be complex enough to be broken down into smaller questions

- help link concepts and principles across disciplines

- correspond to the appropriate time frame

- require materials that are readily available

- be anchored in the lives of learners

- relate to real-world problems

- be meaningful

- be interesting to learners

- be relevant to learners’ lives

Suggested Steps: The Indiana Department of Education has compiled an overview document called Tools for Designing Curriculum through Mapping and Aligning that highlights sixteen “tools” to help school develop, map and align curriculum. An outline of suggested steps to begin a curriculum mapping initiative are below.

For those looking for a deeper dive into mapping and implementation check out the full reports (links below). These pdf documents include rubrics to evaluate current curriculum, software programs, and excellent definitions of terms:

Suggested Steps for How Curriculum is Developed

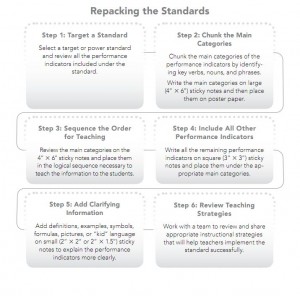

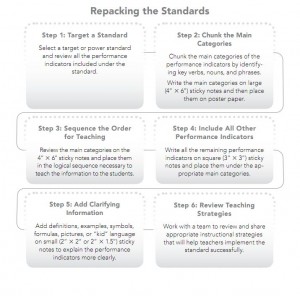

- Teacher Groups Collect Data – This is a time-consuming process, but it provides the foundation upon which the maps will be built. Time must be dedicated to allowing teachers to unpack the standards and reflect on the sub-skills that students will need in order to master the standard as well as time to devise assessments and time frames.

- What are the explicit and implicit understandings?

- What prior knowledge will be needed?

- What content knowledge will be needed?

- What cognitive processes must be fostered (Bloom’s)?

The process may look something like this example I found on Pintrest:

- Group Map Read-through

- Maps are shared

- Maps are critiqued and improved

- Maps are revised

- Mixed Small Group Review

- Group can be comprised across the grades and content areas so that all teachers (including Connections teachers) are part of the process.

- Continue to unpack standards and note findings

- Whole Group Review

- Further Revision based on whole group findings

- Action Plan with respect to long-term planning.